- Home

- Federle, Tim

Better Nate Than Ever Page 2

Better Nate Than Ever Read online

Page 2

“Break a leg,” Libby says, hugging me and giving me a quick kiss on the cheek. “And text constantly, and here”—she thrusts a mysterious manila envelope out at me, pulled from her bag. “Take this, and don’t open it till after your audition. After they fall completely in love with you.”

“Thank you, Libby. I will.” And they won’t.

And from just above, a star blasts a trail across the night sky—like a visor of fire on Libby’s head—leaving it glowing a finger-painted smear, something human and touchable and reachable. Like maybe I could make the same kind of mark in New York, somewhere that might actually understand me.

Maybe Libby wasn’t lying about the meteor shower after all, or can sense things about the future that even I can’t.

“Get right back on the bus, after the audition,” she says. “Don’t go to the wax museum in Times Square or anything. Buy me an ‘I Heart New York’ T-shirt and then just get here. Just get back here.”

I shut the door and roll down the window. The cab smells like a dead person, what a dead person might smell like if ever I’d smelled one. I’m sure I will on this trip, if I don’t end up one myself.

“Libby?”

“Yes, Nate?”

“If anything happens, you were always my favorite Elphaba.”

The cab skids away, and I hold my bag close and shut my eyes and say a frantic prayer that it all goes off okay. And when I turn around to wave to Libby, she isn’t there—just that streak across the sky, still glowing.

Burnt into the Big Dipper like a dare.

Theories on Everything

For the record, I now know why they’re called Greyhound Bus Stations, and it’s not what you think.

They lure you in with the promise of a sweet, fast dog with a cartoon rib cage, but you should just drop the “hound” part of the Greyhound Bus equation. It’s all about “grey.” Everything here is a different color of grey. The hair of the homeless people, even the young ones: grey. The lighting: grey. The hot dogs: grey (but actually pretty tasty). Everything is the color of death, of a foggy day that promises another D-minus on your History homework.

Everything is the color of a wilted flower from my mom’s shop.

God, she’d kill me if she knew I was here.

“And how much is a round-trip ticket to New York City, please?” I say at the counter. I am up on my tiptoes, trying to appear a mildly short boy and not a medically tiny alien child.

“Round-trip,” the guy says, looking half-asleep or perhaps dead; looking grey, “is a hundred dollars.”

“A hundred dollars?” I say, losing my balance and knocking a bunch of Greyhound pamphlets to the floor.

“Yes, a hundred dollars. Or fifty-five one way. But your mom or dad don’t have to pay in cash. We accept credit cards.”

“Funny you should ask about my mom, sir,” I shout. “I figured you might do that, figured this might be the first thing you bring up when somebody as little as me—as little looking as me—walks up to your Greyhound ticket counter, a counter you’re doing one heck of a job manning, to request a ticket out of here.” I’m losing him. I’m losing him. “It’s downright ludicrous, I’ll admit as much, but on the topic of my mom: She’s just in the bathroom. And I’m sure she’ll be out in just a moment, but she’s going through a bit of a stomach ailment and asked that I please take care of my ticket, alone, before she gets out. Because it could take quite a while.”

Libby and I had rehearsed this speech, and perhaps even over-rehearsed it.

“You know stomach ailments, sir,” I say, attempting an off-the-cuff improv.

“You need to be fifteen years old to purchase your own ticket,” the man says, looking above at a TV monitor of the local news. Somebody was just stabbed three blocks from here, which comes as a strange comfort: Perhaps New York will be safer than Pittsburgh.

I pull Anthony’s ID from my wallet, swallow hard, and slide it across the counter. If this man takes an even vaguely close look at this picture—the headshot of an international model, a brother who could be anything in the world he wants (though he’s lying about his height; he is not five foot ten)—I’m dead.

Thank goodness the coverage on the local stabbing is so dynamic—a lot of graphics and eyewitnesses, and one woman is crying and holding a baseball bat, getting great screen time—that the man is riveted, not looking away, taking Mom’s ATM card from my hand and going to swipe it when I stop him.

“Wait!” I say, pulling the card away. “I need to pay this in cash.”

Just what I’d need: a credit card statement arriving for Mom that says ILLEGAL PURCHASE OF NEW YORK CITY GREYHOUND TICKET BY YOUR UNDERAGE SON.

Luckily, I caught him in time.

Luckily, Libby and I prepared for this.

We worked out every covert detail of my trip, yesterday, when she showed up at my house after school. Picture it: I was pretending to rake leaves in the backyard, in actuality smack-dab in the middle of my signature, chore-avoiding Singin’ in the Rain routine (it was pouring out). Libby arrived, panting, breaking the news about the audition in the first place. I get all my headlines from Libby; we still have a dial-up modem at home, and thus all Facebook monitoring is done at her house.

And news she had: “Jordan Rylance”—the lucky twerp across town who goes to the Performing Arts School—“announced a very special trip he’s taking to New York City, Nate,” Libby said, grinning like a Lotto winner. “To audition for a Broadway musical version of E.T., called E.T.: The Broadway Musical Version.” (At that point, I grabbed on to Feather’s tail, for balance.) “And they’re looking for a young boy to play Elliott. And there’s an open call in Manhattan, this weekend.”

And Libby squatted and shielded her face, knowing how I always react to world-shaking news. Knowing I would launch anything on my physical person—coins; old friendship bracelets; the rake—thirty feet in every direction, like a supernova star explosion.

Knowing this was my one-shot ticket out of Jankburg, Pennsylvania.

And now, almost using my mom’s ATM card only twenty minutes into the adventure, I wonder how I could have managed the nerve to think I might pull this off.

I step away from the counter and fish through dollars from my plastic bag full of money, and when I return to pay, the sleepy man has been replaced by a woman who has the same non-look on her face as he did, but with more makeup.

“Can I help you?” She is eating potato chips and they look delicious, by the way.

“Oh, the gentleman before you was helping me, was all set to let the transaction go through.” Cool down, Nate. “But—uh—I figured you might do that, figured this might be the first thing you bring up when somebody as little as me—as little looking as me—walks up to your Greyhound ticket counter, a counter you’re doing one heck of a job manning, to request a ticket out of here. It’s downright ludicrous, I’ll admit as much, but on the topic of my mom: She’s just in the bathroom.” Shut up, Nate. Shut up, Nate. “And I’m sure she’ll be out in just a moment, but she’s going through a bit of a stomach ailment and asked that I please take care of my ticket, alone, before she gets out. Because it could take quite a while.”

The lady continues to eat potato chips. “Okay,” she says, not asking for Anthony’s ID or anything, selling me one ticket.

One ticket to my dreams.

Which costs fifty-five dollars not including tax, these days.

And now I’m staring out the window at a familiar world zooming past, colors bleeding from grey (Pittsburgh) to bright red and blue (a car accident) to brown (somewhere thirty minutes outside of town). Libby shared a really good technique that is thus far working beautifully: Crumple up a bunch of Kleenex and put them on the seat next to yours, and nobody will sit next to you on long bus trips. Try it sometime, guys.

At our first rest stop, only forty miles into the voyage, a man follows me off the bus and into the bathroom, standing right next to me at a urinal. For a moment I wonder what the best way w

ill be to make myself throw up on him when he tries to kill me.

My stomach is empty, after all.

I finish up and turn around, not looking at him, race to the sink, then decide it will be better to have slightly dirty hands than to kill time until he kills me, and as I’m running to the exit he says, “You dropped this outside.” I turn around and he’s waving Libby’s manila envelope, which must’ve slipped from my bag.

This man must be a New Yorker, returning home. Nobody ever helps me with anything in Jankburg, PA.

I practice my smile next.

From the time we leave the rest stop and make it to Harrisburg, capital of Pennsylvania and crawling with criminals, I practice smiling in the face of fear. Anything could happen at this audition. I could forget my words; I could stutter my own name. But if my smile is firmly intact, if I can show that I’d be an ideal employee, someone who’d never cause a problem, maybe they’ll hire me just for the team spirit I’d bring. Twelve minutes into the smiling exercise, my jaw cramps. Underbites are not designed to be overworked or tested.

I have two donuts, for comfort.

A woman in front of me is listening to something loud on her headphones, trendy music that Anthony probably knows, and that would normally irritate me—but tonight, the distraction is pulling me out of my own terrified, self-doubting mind. Her head bops to the downbeat, hair cascading up and over her seat into my lap, and I wonder if New Yorkers have such big hair. Probably not. They probably all shave their heads or have discovered some other trend that is going to be totally intimidating and exciting.

What if I have to get a temporary tattoo at the border, as we’re pulling in to New York Manhattan City Island? What if they stamp my hand like at the underage club Anthony goes to on weekends, and what if the ink is so dark on my pale, lifeless, grey-Jankburg hands that my mom immediately recognizes it: the stamp of a border crosser. Of a bad kid who snuck away.

She’d kill me.

No, she actually would. “Don’t try to run away from home or anything stupid. I’ll kill you if you get yourself killed.”

Actual recent quote.

Okay, I didn’t want to do this, but take a two-minute detour with me. You need to meet my mother. It’s time.

A Quick but Notable Conversation with Mom, a Week Ago

I had both dogs on their leashes (Feather, of course, and Mom’s awful lap warmer, Tippy). We were breaking the front door when Mom appeared next to me, in her big blue parka. Uh-oh.

“Lemme just walk you to the corner,” she said, “and you can take them the rest of the way down past the Kruehlers.’”

Often when I’m walking Feather (alone), I pretend I am Don Quixote and he is my faithful manservant, and we go down to the creek behind the Kruehlers’ house and I sing “The Impossible Dream” at the top of my little lungs. You’re not going to believe me, but I’ve had newts stop and stare.

Before Mom and I’d even gotten out of the front yard last week, she blurted, “So, Daddy is taking me away for the weekend.”

“You’re kidding!” I said, stepping on Tippy (which is somehow short for Tiffany), who yelped like a sticky faucet.

“Yes, first time in seventeen years,” Mom said, with not a whole lot of enthusiasm. Feather spotted something in a bush and got low, his tail parallel to the grass.

“So where are you guys going?”

“The Greenbrier. The Greenbrier in West Virginia. It’s very fancy and expensive.”

Silence. Who knew birds could even chirp so loudly, that was the type of silence they cut through.

“Dad can afford ‘expensive’?” I said, and she glared at me.

“You only celebrate your seventeen-year anniversary once, so, I dunno. I’m not going to question your father.”

“Well. I’m glad for you two.”

“Thanks,” she said, probably happy that someone was endorsing it. Probably worried—as worried as I was—that they couldn’t afford such an extravagance.

She broke away to take Tippy home, to let me walk Feather the rest of the way around the block, and turned back to say, “Don’t get into any trouble around the neighborhood, Nate.”

“Sure thing, Ma.”

“The Kruehlers called last week, to say they heard something wild howling in the woods.”

Oh no.

“They thought a rabid beaver or something was in their yard, Nate, stuck in a bear trap. And it turns out Mr. Kruehler went to the lookout in their attic and saw you in their woods, wailing like an animal, with no regard for nature. And just prancing around like—you know.”

(Like a fairy, right, Mom?)

“It’s just you have to be careful, Nathan.”

I remember it now. I was acting out a scene from Hairspray, with Feather turning in a surprisingly believable performance as Tracy Turnblad.

“People hunt back there, Nate. I don’t . . . it’ll be your fault alone if there’s an accident.”

“Don’t worry about an accident, Mom. Anybody shooting Nate Foster would know exactly what they were aiming at,” I wanted to say, but I just went, “Okay.”

“Same thing at school. You could at least try to take a page from Anthony’s book. To fit in.”

Mom gets a lot of calls from school, where my only good subjects are Creative Writing and Getting Taunted. Take infamous bullies James Madison and his Bills of Rights (that’s two boys named Bill, around whom James Madison specifically created a gang, because of the admittedly clever constitutional tie-in thing). They can’t let a day go by without putting me through the wringer. Most recently, they cornered me after school in the gym and told me I couldn’t leave the basketball court until I made “three three-pointers in a row.” I asked if I could just make “one nine-pointer and be done with it,” and little Bill laughed and said, “He’s not unfunny for a faggot.”

(My sexuality, by the way, is off-topic and unrelated. I am undecided. I am a freshman at the College of Sexuality and I have undecided my major, and frankly don’t want to declare anything other than “Hey, jerks, I’m thirteen, leave me alone. Macaroni and cheese is still my favorite food—how would I know who I want to hook up with?”)

“Are those boys still calling you Natey the Lady at school?” Mom said, her face tired and long.

“No way, Ma.” (They’re actually calling me Fagster, now, a play on Foster. And which I don’t totally disrespect from a humor angle.)

“Well, that’s all, then,” Mom said, scooping Tippy up and letting her lick Mom’s mouth, which gives me the heebs. “Oh, and Nate. Try to keep it down around Anthony, too. He gets very religious-like about his meets, and there’s a big one coming up,” and she was off, back up the hill. “And he’s in charge while we’re away,” she yelled, not even turning to face me. “Don’t try to run away from home or anything stupid! I’ll kill you if you get yourself killed.”

See, I told you it was a direct quote.

That’s all you need to know about that.

This’ll Be Fast: You Might as Well Meet Dad, Too

“I hear you’re taking Mom away for an anniversary weekend?”

“Your brother’s in charge while we’re away.” Dad was doing something with WD-40 and a fishing pole. “It’s important to treat a girl proper every now and then, son.” This from a man who reportedly ran around with an exotic dancer in McKeesport throughout all of last winter, according to Mom’s diary. The parts I could read. The parts not smeared with rain or maybe tears, I guess.

“I’ll keep that in mind.”

“You meeting any nice girls at school, son?”

“Dad, I’m thirteen.”

“Can’t start too young.”

That’s all you need to know about that.

“Met your mother when I was your age.”

I said that’s all you need to know about that.

“I’m prayin’ for you, boy.”

Seventy-Seven Miles to Manhattan

But forget my parents.

(Do it for me. Si

nce I can’t seem to.)

With the Greyhound wheels thumping a trance, I close my eyes and nod off, imagining what it’ll be like in New York when I arrive. In my mind, Kristin Chenoweth will be waiting for us on a staircase at this Port Authority place, probably singing the theme to “New York, New York.” And then someone’ll hand out handguns and cans of Mace and tell us, “Good luck, and have the time of your life if you can keep it.”

Somewhere in the middle of New Jersey, a collection of drool has pooled so impressively onto my shirt that a child in another row wakes me with his phone’s camera flash. It doesn’t bother me, though; people are already taking my photo and I haven’t even arrived at my dream destination.

And when the blur in my eyes finally vanishes, I see it, sticking up like a hitchhiker’s thumb. Or better yet, like a big middle finger at Jankburg.

The Empire State Building.

Where I bet you need a shot of oxygen by about the thirtieth floor.

By the time we’re spinning through the Lincoln Tunnel, a woman across the aisle has caught sight of my face, of my open jaw and flitting eyebrows, and calls over, “You’ll never forget it. You’ll never forget the first time,” and I turn away and whisper to the window, “You don’t have to say that twice.”

And we arrive at Port Authority.

And I am lifted into the terminal.

(It’s annoying to say it like that, but I’m reporting in with hard facts and was raised a partial-Christian and thus can’t lie about things like hard facts.)

I and my belongings are lifted into Port Authority Bus Terminal.

I’m actually holding my bookbag so tight, it probably looks like an extension of my shirt. Or like I have a horribly distended belly, like an abscess, and have ventured to New York for surgery at one of their world-famous belly abscess hospitals.

There is such a rush into Port Authority, exiting the bus and then mazing through a series of escalators, that all I have to do is lean just slightly back and the crowd literally surges me along. This must be what it feels like when you’re my brother and you score a goal and the team carries you across the field.

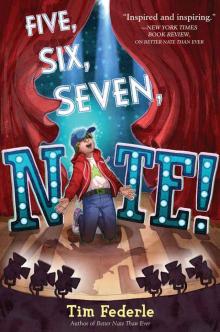

Five, Six, Seven, Nate!

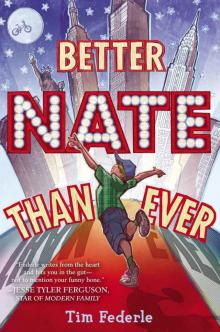

Five, Six, Seven, Nate! Better Nate Than Ever

Better Nate Than Ever